BY: admin

Uncategorized

Comments: No Comments

WORLD AUTISM UNDERSTANDING DAY

WORLD AUTISM UNDERSTANDING DAY

Aamina Shakoor, Speech Pathologist, Change for Life.

What is World Autism Understanding Day?

Every year, on the 2nd of April, the world celebrates World Autism Awareness Day. However, Autism Advocacy groups have been focussing shifting away from the word ‘awareness’ and using ‘understanding’ or ‘acceptance’ instead. The reason behind is this that language used to talk about Autism and Autistic people is very important. World Autism Understanding Day celebrates the resilience of those affected by the disorder and supports causes that promote awareness of it.

What is Autism?

Defining Autism is a little tricky. Autism is a developmental condition that can affect how an individual learns and interactions with everyone around them. Autism has many different characteristics; therefore, Autistic people are not the same and are different in their own ways. Therefore, Autism is described as a ‘spectrum’.

How many people are on the Autism Spectrum?

According to Autism Spectrum Org “research suggests that an estimated 1 in 70 people in Australia on the autism spectrum”. Autism can be diagnosed in people from all cultural and economic backgrounds. The characteristics of autism may appear in early childhood, but sometimes they can go unrecognised until later in life

How to be an Ally to Autistic People:

- Listen to Autistic voices

- Support Autistic-led organisations

- Collaborate with autistic people on information that is about them

- Use ‘autistic’ vs ‘person with autism’ – this is preferred

- Ask questions if you aren’t sure about something.

BY: admin

Uncategorized

Comments: No Comments

How to read a book

How to read a book.

By Michael Audas.

It is important for children to read a vast quantity—and wide variety—of different books. Not only does this allow them to develop familiarity with different text styles, but it also exposes them to a cornucopia of new words and ways to use language. Sometimes, however, our zeal for certain quantitative metrics (e.g., how many books has Johnny read?) can overshadow the considerations that go into a quality engagement with reading. When we find ourselves rushing through a book to ’get it done,’ or because we sense that our young reader’s interest is flagging, we can be sure that we will have deprived her or him of the real treasures stored within a given work, unless we correct our course.

But how can we go about this? The first and most important thing to consider is speed: this doesn’t merely mean that we slow the cadence of our reading, or that we stop at encouraging the child to do the same, but rather that we approach a text as if we were in no real hurry to put it down. We should not expect a book to yield its riches any more than we would invite someone to tell us their life story—but only within a fixed timeframe. Getting to know a book, just like getting to know a person, requires that we spend the time to ask meaningful questions and that we wait to hear the answer in full; if we still don’t understand, we need to ask more questions, and/or think about it until we do.

Of course, a book will not always be so charitable as to answer verbal questions with a verbal reply, but this is where children are fortunate enough to have someone on hand who can do precisely that. Better yet: if a parent’s answer shows the child (and yes, they can tell) that they are thinking long and hard about a book, and that they are on the same journey of understanding as they, then the message they will receive is “this book is worth reading, because even my super-smart Mummy or Daddy is trying to figure it out!” Even a passage with very many unfamiliar words, or poetic flourishes, can be made comprehensible to an early reader if an adult is on hand to provide a well-considered explanation.

But children, just like their statistically-taller counterparts, can also be quite prideful. They may not want to admit that they don’t understand something. That’s where the parent or adult needs to be vigilant and anticipate areas of difficulty and address gaps in understanding. The support you can offer in this regard is incredibly valuable, especially when approaching older texts which, while infinitely worth the reading, are often difficult for children to parse due to their complexity and archaisms.

Restful reading at a slow pace, and driven by a spirit of genuine curiosity counts for far more than how many books your child’s bookmark has hopped between in a month.

BY: admin

Uncategorized

Comments: No Comments

5 Belly Breathing Exercises for Emotional Regulation

5 Belly Breathing Exercises for Emotional Regulation

By Stephanie Cordingley – Provisional Psychologist

When experiencing intense or uncomfortable emotions (most commonly stress or anxiety) try paced belly breathing. Paced belly breathing helps us calm our bodies which helps us calm our intense emotions, so we feel safe and in control. Proactively model and practice using this strategy with your child, that way they can learn to use it as a calming strategy. A starting point is using it after exciting activities, for example playtime or sports, to help calm the body ready for the transition to the next activity or home.

BY: admin

Uncategorized

Comments: No Comments

Importance od Play Skills

Importance of Play Skills

Aamina Shakoor, Speech Pathologist, Change for Life.

Why are Play Skills Important for Speech and Language?

Play skills are significantly important when it comes to a child’s speech and language development. Play provides some of the earliest opportunities for a child to develop their social skills as well as forming symbolic relationships. These areas allow children to later develop higher-language functions.

Play allows children to learn to navigate and react to their environment. Play skills are also foundational for the development of higher-level speech and language functions, such as conversational turn-taking and problem-solving. Play is essential to development because it contributes to the cognitive, physical, social, and emotional well-being of children and youth.

How to Facilitate Language Development Through Play

Play activities are an important part of your child’s life, and your child will want you to be a part of these activities. This is also an opportunity to help your child develop important language skills in fun and supportive situations.

Pepper and Weitzman (2004) recommend the following strategies:

Follow your child’s lead

An individual’s interest level often determines how engaged he becomes in the activity. Therefore, it is important to become observers of your child’s play and engage them in play activities that they find interesting. Increased child engagement allows greater opportunities for language acquisition.

Practice turn taking

Establishing successful turn-taking routines will facilitate social and communicative skill development in young children. Turn taking is a skill that can easily be promoted through play with children of any age. Offering a brief pause when it is his turn will increase your child’s initiation, communication, and independence.

Modelling language

Modelling language for your child provides exposure to new vocabulary and correct grammar while speaking. Play is an excellent opportunity for a child to attach meaning to words and build vocabulary. Providing accurate language input can include commenting about what you or your child are doing, adding a word or phrase to the child’s short phrases, exposing your child to synonyms, or by modelling the correct sentence structure.

Read books together

Books are filled with opportunities to facilitate language skills. While reading stories that are familiar to your child, you can develop speech, language, and memory skills. Expose your child to a variety of books and watch to see what books he/she prefers. By following your child’s lead, you will capture his attention. Initially, you should read books with simple pictures and simple text. Consider board books, pop-up books, books with textures, and other interactive books.

BY: admin

Uncategorized

Comments: No Comments

Being Bilingual

BEING BILINGUAL

Aamina Shakoor, Speech Pathologist, Change for Life.

People who use two languages are often referred to as bilingual and those who speak more than two languages may be referred to as multilingual. A second language can be learnt either simultaneously (at the same time) or sequentially (preferred language first, then second language).

Children who learn more than one language at a time require more time to develop their overall expressive language. However, being bilingual can result in an individual being more connected with their culture, have an increased self-esteem, a greater sense of community as well as more complex thinking skills (Rosenberg, 2002). The earlier that children are exposed to both languages, the easier it is for them to learn the language as well as retaining the native accent. The longer you wait, it is likely for them to be less fluent.

Instead of immersing a child into a second language, it is more beneficial to slowly introduce them. Below are some ideas of how this can be achieved.

Give plenty of opportunities.

The more a child is exposed to a language, the better he/she will become at using and understanding it. Give your child many opportunities to speak and hear both languages in different situations and with different people.

Slow down.

Try not to talk so fast. This doesn’t just apply to parents of bilingual children. Kids will have a much easier time picking up what they hear if you speak at a slower pace.

Set Boundaries

Help your child tell the difference between the languages by having clear boundaries (e.g. using home language with family and English at the shops).

Story time.

Read books in each language to help your child develop reading skills while building vocabulary, sentence structure, phonemic awareness, and learning about the related culture.

How do I teach my child two or more languages?

To be successful in teaching your child two languages it is essential to have a “family language policy”. This is a plan for who will talk to your child in what language and in what context. For example, some families have a “one parent, one language” policy meaning that one parent speaks only in one language (e.g., Spanish) while the other speaks only in English to the child.

Things to remember with bilingual children:

Bilingual children generally develop language the same way. They may proceed through a sequence of learning stages:

- Initially they may go through a silent period while they are listening and learning new words.

- They will develop language at the same rate as children learning one language i.e. first words around one year and joining words together around two years of age.

- When learning to talk, children may mix grammar rules, or their sentences may contain words from each language.

References:

Rosenberg, M., (May 2002). Raising Bilingual Children, http://www.aitech.ac.jp/~iteslj/Articles/Rosenberg-Bilingual.html

www.speechpathologyaustralia.org.au/bilingual

www.youtube.com/SESLHD

BY: admin

Uncategorized

Comments: No Comments

Great Books for Reinforcing Language work

Great Books for Reinforcing Language work

Michael Audas – Speech Pathologist

When your child works on language goals with a speech pathol- ogist, it tends to be within the context of very specific, structured activities. Being able to carry out these same activities at home is a great way for children to practice and make progress towards their language goals, but, given the complexity of the activities, and the limitations on time, that isn’t always possible.

Here, then, are some great books that your child will enjoy reading, but which will also reinforce some of the language con- cepts that they may have been working on in therapy.

Prepositions

– Polar Bear, Polar Bear, What Do You Hear? by Bill Martin, Jr. E.g., “I hear [sound] in my ear.”

– One Gorilla, by Atsuko Morozumi. New prepositions on each page.

Negatives

– Green Eggs and Ham, by Dr. Seuss. E.g., “I do not like them.”

– Have You Seen My Cat, by Eric Carle. E.g., “That is not my cat.”

Verbs

– I’m a Hungry Dinosaur, by Usborne. E.g., shake, stir, pat, smooth.

– The Little Old Lady Who Was Not Afraid of Anything, by Linda Williams. E.g., wiggle, shake, clap, nod

Plural Nouns

– Wombat Stew, by Marica Vaughan. E.g., soft feathers, crunchy flies.

– Farm Babies, by Rod Campbell. E.g., two lambs, three pup- pies.

Adjectives

– Dinosaur Roar, by Henrietta Strickland. E.g., bumpy, smooth, grumpy, sweet, clean, dirty.

– Alexander and the Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day, by Judith Viorst. E.g., terrible, horrible, scrunched, smushed.

BY: admin

Uncategorized

Comments: No Comments

Great Games for Reading and Spelling

Great Games for Reading and Spelling

Michael Audas – Speech Pathologist.

Reading and spelling are not ’natural’ skills for any child to acquire. Unlike learning to walk, learning to speak, and so on, the decoding of words and their constituent alphabetic characters into sounds requires more than just the right kind of environmental stimuli to be present. That being said, a lot of kids do acquire the necessary knowledge and skills for reading and spelling with very little in the way of explicit instruction concerning spelling rules or letter-to-sound correspondences.

Struggling readers and spellers, however, do require explicit instruction, and drills, and quite a lot of both. An amount which quickly becomes tedious for them, in fact. But that doesn’t mean that there aren’t fun ways for these same children to improve their reading and spelling—ways that can help break up otherwise- monotonous phonics drills and the like. In fact, when you play these games with your children, they’ll be having so much fun they won’t even realise they’re working on academic skills!

BY: admin

Uncategorized

Comments: No Comments

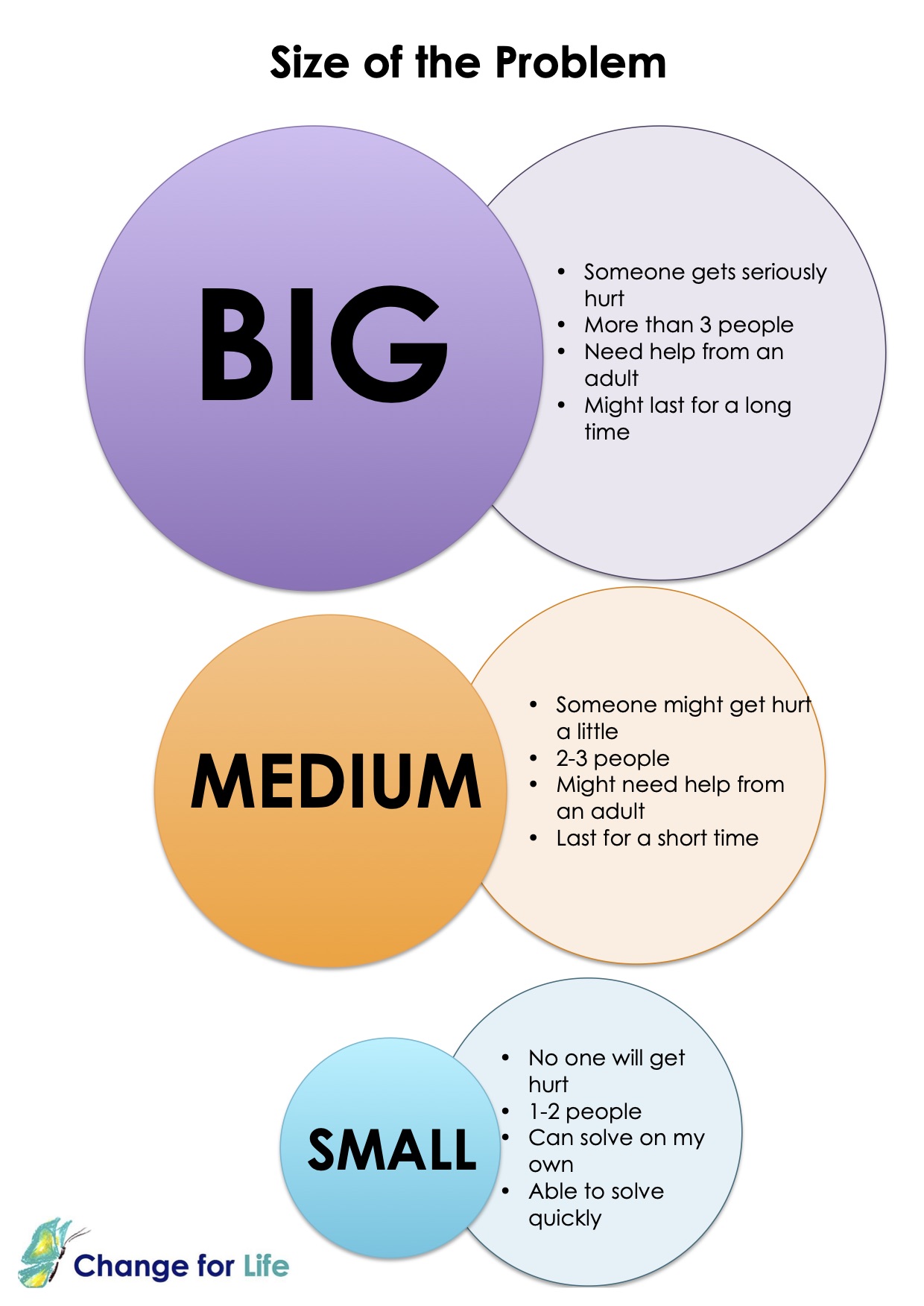

Size of the Problem

Size of the Problem

Melanie Chan – Psychologist

Supporting our kids to recognise the size of the problem can help teach them to respond appropriately to different problems. When we are faced with a small problem, we can respond with it with a small reaction! When there is a bigproblem, what is an appropriate big reaction we can have?

Here is a little guide that I’ve been using with some of my clients to help identify which size our problem is and how we can respond in a helpful way.

BY: admin

Uncategorized

Comments: No Comments

Why is sleep important?

Why is sleep important?

By Stephanie Cordingley – Provisional Psychologist

Sleep is needed to maintain and improve our mental health and wellbeing. It helps improve our attention, learning, memory, and behaviour, as, our body and mind can rest and repair. Sleep is like food for your brain! Most of us need at least 8 – 9 hours of sleep per night.

To help you sleep better try turning off electronic devices at least 30 minutes before bed, enjoy some exercise during the day, develop a quiet and soothing bedtime routine and get any worries off your mind by writing them down before going to sleep.

BY: admin

Uncategorized

Comments: No Comments